The head of the International Energy Agency declared in the Financial Times that all fossil fuel consumption will peak this decade. This would have been a big news item five years ago, but just about everyone is prospecting for peaks these days. The Gregor Letter for example downgraded oil coverage some time ago—while still keeping tabs on global consumption—and the focus here has moved on to the far more important question: how much longer do we have to wait before decarbonization finally delivers emissions declines. The current answer on that uncertainty is not so promising, unfortunately.

The IEA head, Fatih Birol, has a tendency to use imprecise language when talking about the tricky categories of growth, peak, and decline, and his piece in the Financial Times was no different. In the lede, he cites decline rhetorically, dangling that outcome as unappetizing to the coal, natural gas, and oil industries, but an inevitability nevertheless. Well of course. But then the article, further down, admits that the declines, when they come, will themselves not be linear. That sounds like a mild acknowledgment of reality in post-peak periods: rough and lengthy plateaus that don’t convert easily to declines. As always, intuitions assume declines follow imminently after peak. But at the scale of the global energy system, that is simply untrue. Let’s be clear: peaks rolling over quickly into declines are not observed. Overall, Birol’s FT piece follows this intuition, and that is either an error of analysis, or of writing, or both. While it’s true that achieving peak is a necessary goal, it is not sufficient to solve the problem. And that reality becomes more acute, actually, as we now approach peak consumption of the main fossil fuels. Hunting for peak five years ago, when it seemed impossible, was a worthy game. But peak is no longer the play.

Meanwhile in the US, the EIA is now forecasting that gasoline consumption is headed for mild decline. Wonderful. It only took twenty years from peak. According to the latest STEO report:

We reduced our U.S. gasoline consumption forecast because the U.S. Census Bureau revised its population estimates for the United States to include fewer people of working age and more people of retirement age, who tend to drive less. The revised population estimates have also resulted in a downward revision of our vehicle miles traveled (VMT) forecast, which directly affects motor gasoline consumption. We forecast U.S. gasoline consumption will average 8.9 million b/d in 2023 and 8.7 million b/d in 2024.

The Gregor Letter has previously taken the view that California gasoline consumption finally fell off its own plateau after twenty years also, and is now in decline. The natural next-step would be to see US gasoline consumption also fall into decline. But we’re too early in EV national adoption, and we have no national policies penalizing existing fuel consumption. In the chart below, notice how gasoline demand has been “peaking” for nearly twenty years also, on a national basis.

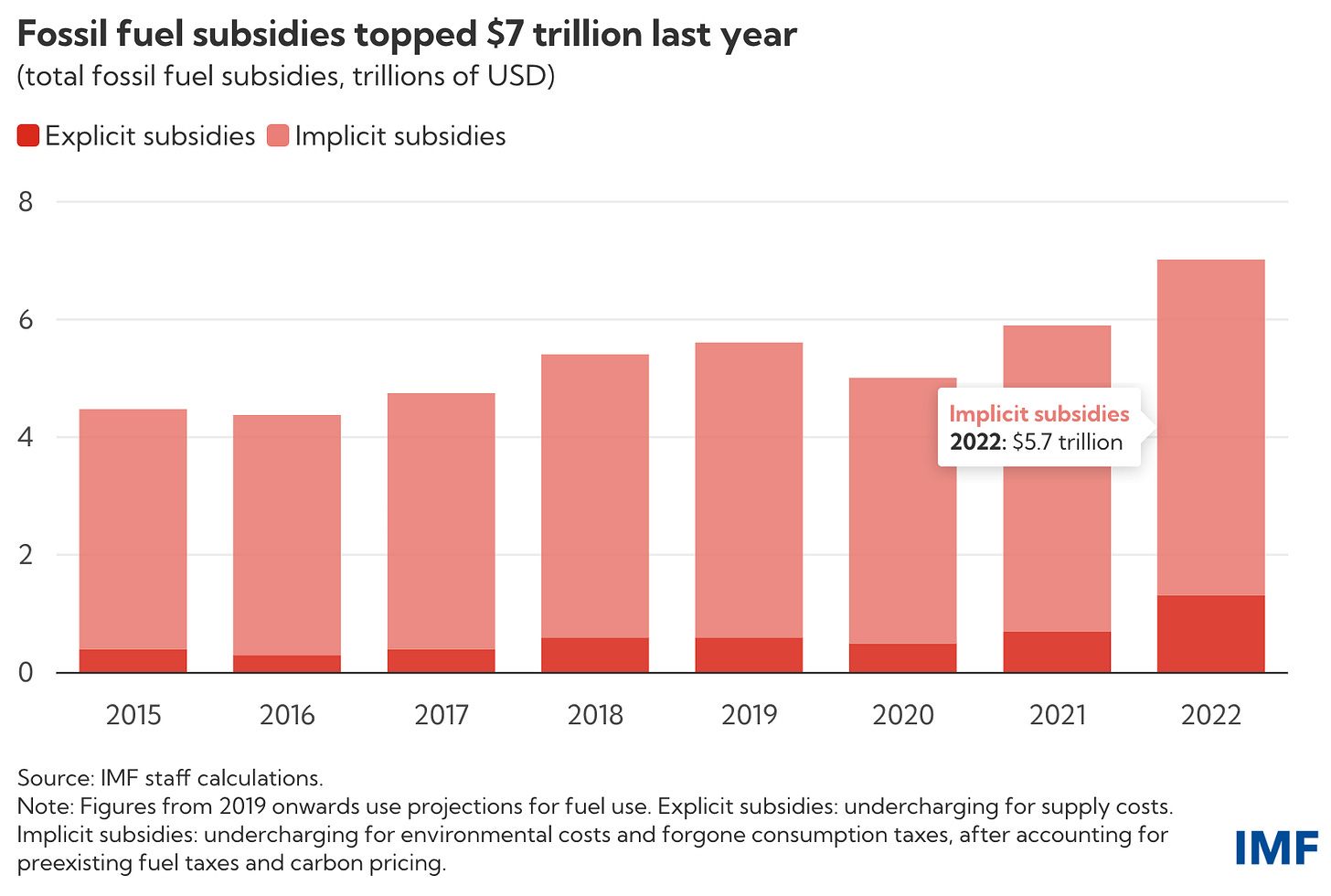

Quantifying indirect subsidies to global fossil fuel industries is absolutely the right analytical approach. To get the true picture of how path dependency is maintained within coal, natural gas, and oil systems, one has to focus not on subsidies to extraction, but subsidies to consumption. The IMF has done just that in their latest report. Let’s first take a look at the big picture:

Notice the huge spread between explicit and implicit subsidies. That’s another way of portraying the fact that the systems we subsidize to consume fossil fuels are far larger than the fossil fuel production system itself. The most obvious example: the transportation and travel sector, now the top sector for emissions in the US, and the second place sector for emissions globally.

The IMF fingers the problem correctly, noting that untaxed air pollution and untaxed emissions are the main source of indirect subsidies. They write in their report:

….undercharging for local air pollution and climate change accounts for about 60 percent of total fossil fuel subsidies in 2022, undercharging for broader externalities and supply costs another 35 percent, and the remainder undercharging for general consumption taxes.

What would a proper scheme look like, for road transportation? Imagine every city in Europe and the US adopting London’s road-charging scheme, which started out twenty years ago with fees on trips, but has subsequently expanded outward to apply fees based on the emissions that come from fuel and car types. If you meet the emissions requirements, no extra charge. If you don’t, well, pay up.

After maintaining a strongly negative stance for many years on wind and solar, perhaps it’s time for Bill Gates to admit he was wrong. The new Elon Musk biography by Walter Isaacson apparently contains a revealing quote from Gates, demonstrating he has not evolved even a little on this question. As reported by CNBC:

Gates argued that batteries would never be able to power large semitrucks and that solar energy would not be a major part of solving the climate problem. “I showed him the numbers,” Gates said. “It’s an area where I clearly knew something that he didn’t.”

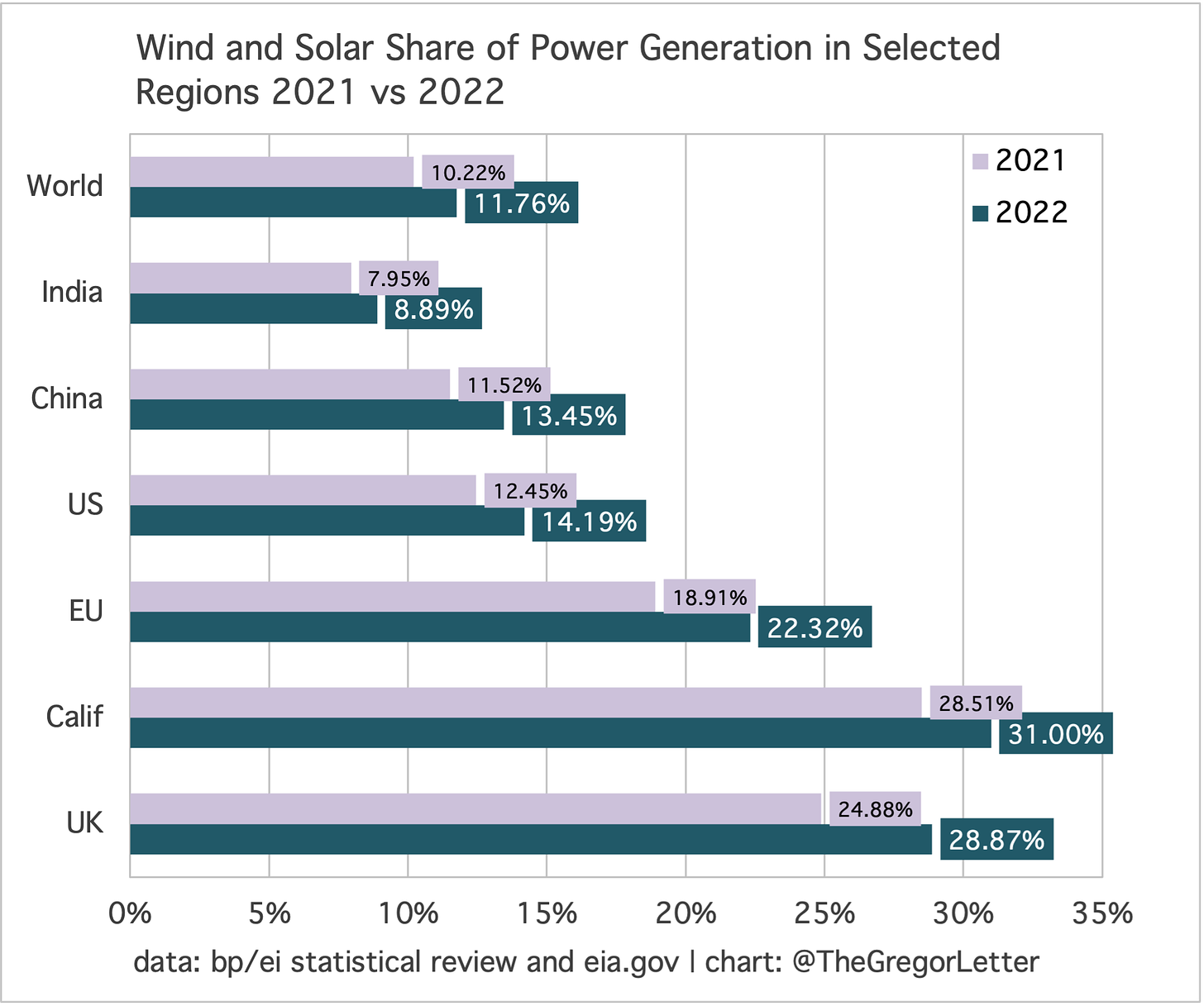

Oof. If that sounds bad, it’s actually worse than all that. Since Gates took his stand against wind and solar’s ability to do much to solve climate change, the two technologies have stormed the gates of the city, so to speak. Ha. So Gates is even more wrong today than he was when he started voicing this view last decade. Look at these numbers:

Just thinking about loud, but perhaps wind and solar know something that Bill Gates doesn’t.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.